Disagreement in Service of Heaven

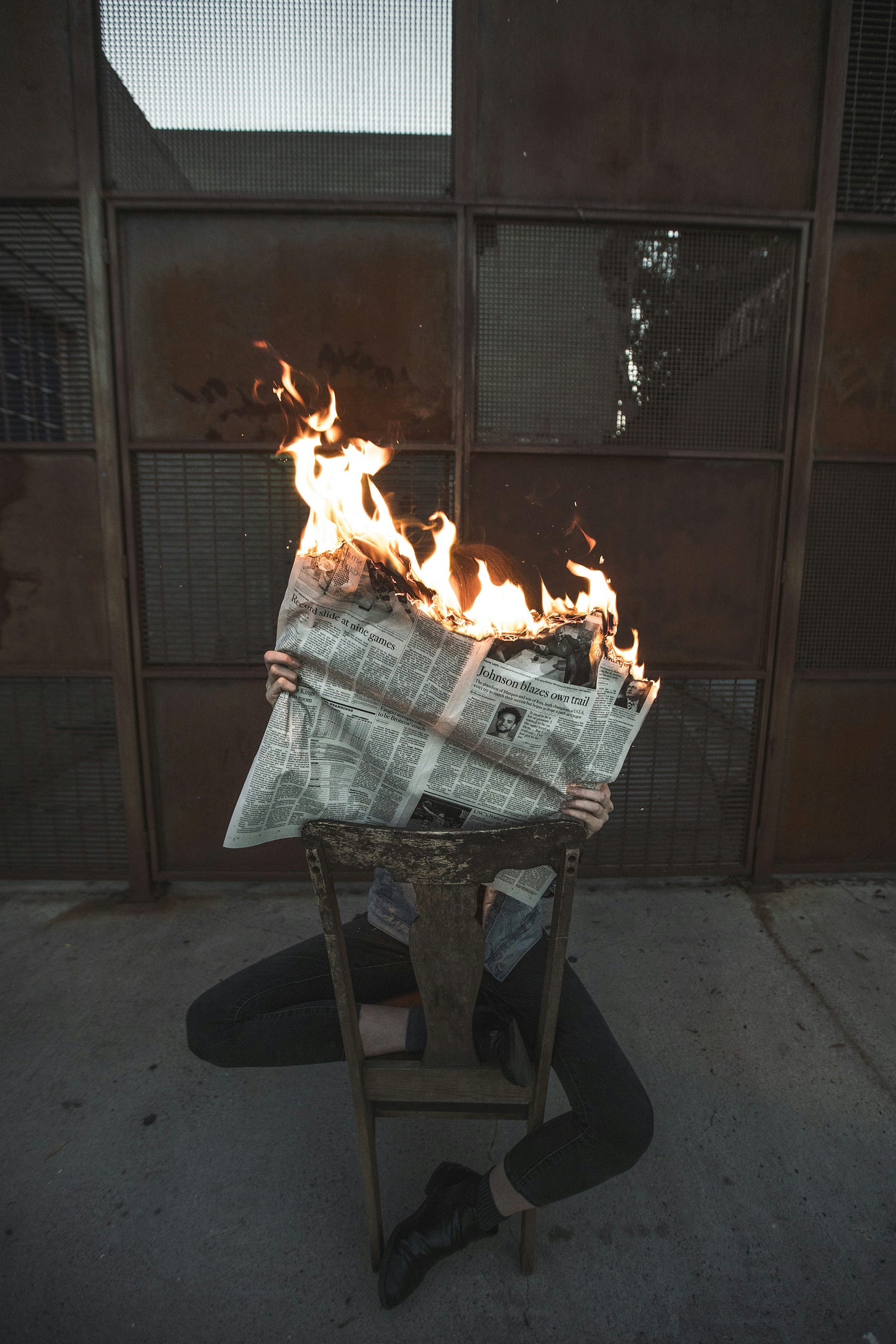

Battle lines are drawn in times of war, but truth is rarely one-sided.

First off, apologies to my dear readers for the gap in missives. The past month has had some professional and personal highs and lows — some of which I hope to reveal more publicly sometime! This week I’d like to share something a little out of the norm from my usual “Internet Culture” missives.

In these times, I’ve sat scrolling the news and social media with an understanding that so much of I’ve been seeing is somebody’s propaganda. Very little of it feels satisfying as an explanation or even rallying cry. There are such clear battle lines drawn in press and politics (some quite literal) that the binary can feel both predictable and suffocating. After all, war forces combatants into sides through violence, even if there are many truths at once.

And yet in this time, I’ve had some of the most nuanced offline conversations about war, religion, geopolitics, identity, progress, and time.

In moments of psychic unrest such as these, we may try on different ideas, passions, or viewpoints that we might not have before in order to make sense of the world. In that respect, I can see why great art has also been produced in times of great pain. There is sense-making going on that is not yet “rational” or “commonsense” that could define the next era.

Yet at the same time, I personally ascribe these deeply probing conversations to skills developed in a fellowship I did through the Pardes Institute for Jewish Studies called “Mahloket Matters.” Roughly put, a mahloket is a debate, a disagreement. Over the course of many weeks, we attended lectures and did exercises exploring mahloket through religious, sociological, and psychological lenses. When can you “agree to disagree?” When must a boundary be put up? When does verbal communication no longer function effectively?

Mahloket l’shem shamayim is a highly revered Jewish concept meaning “disagreement in service of heaven.” In the strictest of terms, such a mahloket describes what we might call a “good faith” disagreement between people who share some core values. For example, disagreeing about whether or not one should keep the sabbath is not a disagreement in service of heaven among the ultra-religious, but disagreeing over the intricacies of those laws regarding the sabbath is a mahloket in service of heaven.

Yet, the concept of mahloket has teachings beyond Jewish legalistic debate because truth is understood as being multifaceted and not ever fully knowable. In Judaism, truth is described as having 50 panim, or faces, 49 of which are visible to humanity (only Gd can see them all!) so naturally, disagreement will occur between the mere mortals who can only see a few faces.

I should note that other faith traditions have similar concepts of truth. Anekantavada is a Jain epistemological doctrine that translates roughly to “non-one-sidedness doctrine.” It is an understanding of truth as “maybe,” that no single truth can be stated to absolutely describe existence.

Our ability to approach one face of truth is different depending on the lens, position, interests, or stances of an individual or even a culture. So how to better have disagreement?

Two Rabbis Walk Into A Cafeteria

With the support of Pardes, I put together a gathering of young professionals of varying levels of Jewish identity and observance to listen to the talks of two local rabbis, Rabbi Jorge and Rabbi Samy to introduce the idea of mahloket as a tool for better disagreement and conflict in our lives. Rab Jorge started with thinking about how mahloket impacts us internally, as individuals, Rab Samy considering larger social ramifications. Both spent time considering how we need to see other parts not just of ourselves, but also seeing the world through the lens of others.

Rabbi Jorge pointed out that the word "heaven,” hashamayim, holds an internal, holy mahloket: the word is comprised of the Hebrew words for fire and water. Whether body and soul, light and dark, complete systems hold internal contradictions. Within ourselves, there are contradictions — to say nothing of others. These contradictions may emerge over time as well — what a child can see close to the ground is very different from what an adult can see standing at over 5 feet. Sometimes we have to get on the level of others to understand their truth. This is clearly more easily said than done.

Rabbi Samy started by reminding us that mahloket implies truth has many faces. This reminder helps us most often times in our marriages, in raising children. Telling a child “You don’t know what you are talking about” may shut down someone who is trying to express an experience they are having of the world. You may not like how they say it, they may be repeating something they heard you don’t like, but communication is a form of data. Why shut out a data point of truth? Do we seek truth? Or do we seek comfort? Control?

I’m not doing these learned Rabbis much justice in regurgitating their speeches here. But I highlight these two examples of much larger speeches to articulate the value of listening to what someone is saying as a way of seeing their world, their truth.

Of course, sometimes rational conversation shuts down. Lines are crossed. This is when your toddler has a tantrum. When you shout at your husband. When a country goes to war. People fight to be expressed and heard until they are seen and heard. Can we hear signals before they become deafening? Did we hear the debate before it became a fight?

Final Thought

I come back to the start of this piece: a time of war where sides are fighting but there are many truths. The way I see it, the binaries that got us to the standoffs we find ourselves in have proven to not create peace, but have created more solidified struggles—not resolutions. Realizing that such a standoff can have blood consequences has allowed so many people who may not directly be in the line of fire to question the language, rhetorics, or systems they have assumed to be true or in their interests previously. Examples, you ask? This could be liberal and even lefty academics questioning if the language of “safetyism” they once embraced was worth it, considering it may have stifled free speech more than protected it. This could be conservatives wondering if throwing all their support behind one man in exchange for power was a wise move in the long run for their party. Does absolutism (in markets, labor, health, agriculture, pro/anti regulation, security) deliver the good life?

This missive does not have some grand conclusion. I offer the concept of mahloket only as a way to resist seeing clear “one-sidedness” as a declaration of absolute truth. The terrible thing you see about your favorite politician may be true, just as much as the thing you love about them. The righteousness with which your side goes into war may be just, but it could also be terrible all at once. Truth does not merely serve one interest, but you should be clear to yourself about what your interests are and who shares them. Often interests are more complete-looking than truth.