The Authenticity Gap

The key to understanding the break in reality so many of us have felt, and how political, cultural, and spiritual entrepreneurs take advantage of this.

When our expectations of reality—shaped by the stories we collectively tell ourselves about how the world works—no longer align with our lived experiences, reality itself can begin to feel like it’s unraveling.

I’ve started calling this distance between expectation and experience the Authenticity Gap—a term that now surfaces regularly in my professional, academic, and even personal life.

For much of my Millennial adulthood, this gap has seemed to widen steadily. The fault lines cracked open for me somewhere after 2008, with “the Financial Crisis” and the enduring permutations of the so-called “War on Terror.” Maybe it’s because I was a middle-class white girl raised amid the short lived neoliberal, deregulatory prosperity of the 1990s and the moral clarity of post-9/11 America. I assumed our better angels would prevail in a United States at the so-called end of history—so long as the government didn’t get in the way (or so I was told in my libertarian-leaning home).

But the markets and the laws didn’t fix themselves. There was no invisible hand restoring order or evenly weighted scales of justice. After the ‘08 crash, people lost their homes and pensions—yet no one went to jail. The War on Terror drained youth from my hometown, only to return them traumatized, greeted by an onslaught of legal (and illegal knockoff) opioids approved by the FDA—and defended by “America’s Mayor,” Rudy Giuliani. These overlapping crises—of financial collapse, endless war, and addiction—have been too quickly forgotten by pundits eager to blame Trump’s rise on Joe Rogan.

Americans looked around and realized the stories they had been told no longer explained the world they were living in. And the leaders, both Democrat and Republican, they once trusted to tell those stories had presided over a political order already being disrupted—whether by design or decay (as I’ve explained here).

To fill this “Authenticity Gap,” new personalities with new stories stepped in. Some were right-wing media impresarios: a few in the populist mold of Pat Buchanan, others inspired by anti-Enlightenment Traditionalist thought, and still others fueled by outright racism. On the other side (though less coordinated), emerged voices from the old Left: democratic socialists, naturalists reviving Indigenous worldviews, even flat-out communists.

They affirmed that what the government or experts or “The Media” had told you was a lie and that this dissociation between what your expectations and what you lived was real. Into that breach came new, but loose deep stories, patched together with “vibes” but propelled by grand epic narratives about “taking the country back from the elites.”

That is what closing the Authenticity Gap looks like. But are there other ways?

The Authenticity Gap is an evolving concept I first began using in consulting—working with everyone from Fortune 500 companies to advocacy groups and nonprofits, all grappling with the same question: why wasn’t their messaging about social impact… having impact? I used it in conversations with journalists who came to me for help fact-checking “misinformation” but left with a whole new way of understanding narrative in politics. It is a tool I’m developing for my forthcoming book.

So consider yourself lucky—this post is an early look at the concept of the Authenticity Gap and how it can be applied to a range of issues: economics, patriotism, foreign policy, health, and spirituality. Bridging this gap takes more than just “vibes politics.” It takes new messengers and new deep stories across every layer of society.

Closing the Authenticity Gap is the work of a generation. So let’s look at it.

Why Authenticity?

Everyone is obsessed with “authenticity” these days,—though, in truth, they’ve been chasing it for most of modern and postmodern times. The quest for authenticity, in many ways, is a nearly violent psycho-spiritual reaction to the norms of a prevailing order that no longer feels applicable. You can see this pattern across centuries: the 19th-century Romantics expunging the fakeness of Victorian stiffness; the disorientation of the Industrial Revolution and urbanization; the 1960s counterculture trying to find true love and freedom in a buttoned-up, war-making world; and now, our influencer-obsessed digital culture, seeking “authentic” voices to tell us “how it really is” instead of relying on the supposedly deceitful elite.

I could have called my “gap” the Reality Gap and focused simply on what is or isn’t real — but what does that mean anyway?But I think Authenticity Gap evokes this social dynamic of trying to find something that realigns our personal and collective stories with lived reality. Each generation must find its own authenticity, in a way.

Cold War literature scholar Lionel Trilling traced the evolution from sincerity to authenticity in 19th-century literature. Sincerity, for Trilling, was “the congruence between avowal and actual feeling”—a required development in modernity for building a functioning participatory society. Yet placing such value on sincerity can mean people will try to “pretend” sincerity to get ahead — a “true” self is hiding behind that act. This dissociation birthed the idea of authenticity, or a “true” self that can be discovered from within, often in opposition to mainstream society; one can be authentic without always being sincere. One could be authentic, Trilling argued, without necessarily being sincere.

Philosopher Charles Taylor expanded on this, noting that modern ideas of authenticity are marked by three features:

the creation or destruction of an existing order,

the pursuit of originality, and

opposition to mainstream norms or morality.

In other words, there’s a kind of playbook for what authenticity looks like—even when it claims to reject convention.

Modern digital technologies have spawned an entire literature around the performance of authenticity—especially as individuals sought influence in a time when traditional institutions were faltering. As trust in elites eroded (as it nearly always does with each generation), authenticity became a new kind of capital. Predictably, the powerful—brands, politicians, celebrities—rushed in to manufacture and monetize it.

It is almost mainstream knowledge that cultural, political, or economic actors trying to offer something “real” will go through great lengths of what communications scholar Michael Serazio calls, “performing-not-performing.” The efforts towards creating sprezzatura, or studied carelessness, in “real” life on the Internet can be a full-time job. Sarah Banet-Weiser writes how in modern times our “inner worlds” that might be seen as our most “authentic” spaces (identity, creativity, politics, religion) have been cultivated as “branded spaces,” identified with powerful figures, companies, and movements in a capitalist world.

But beneath it all, the longing for authenticity taps into something even deeper than market dynamics. It calls forth our most primal desires. Perhaps that’s why the social media platforms designed to “deliver authenticity” so often end up feeding us the most libidinal content: war, misogyny, racism, suffering, humiliation. In this logic, what feels raw and real is what forces us to confront who—and what—is actually on our side.

Etymologically, a lot of dictionaries will tell you that “authentic” comes from Greek αὐθεντικός for “original” or “genuine” but this word comes later in the evolution of the language. Dig deeper—and if you’re me, ask your high school classmate turned classics professor—and you’ll find it traces back to αὐθεντής. This term is sometimes translated as “one acting on one’s own authority,” but in classical texts by Herodotus, Euripides, and Thucydides, αὐθεντής is more starkly rendered: it means “murderer.”

At the root of what feels authentic is, in fact, a kind of violence—a radical self-assertion. The taking of authority. The taking of life. In this light, the yearning for authenticity—when it seeks to rewrite the world’s stories and remake its structures—can become psychically, politically, and sometimes actually violent.

Deep Stories, Unraveled and Rewritten

Coined by sociologist Arlie Hochschild in her ethnography of Southern conservatives in the early aughts, a “deep story” is an ongoing narrative that captures both the sentiment and emotion of a community. It doesn’t have to be true, but it does have to ring authentic. It is a kind of commonsense explanation for how the world works. Some of our deep stories have been unraveled in the past 30 years. They need to be rewritten.

The Unraveling

There was a story in the second half of 20th century America. It went like this: you live in a free country with free markets. If you put in the effort, go to college, and work hard, you can improve your station in life — buy a house, support your family, live well, retire. Despite differences, we can expect equal treatment under the law. The government is by and for the people, so it will try its best to improve. America is a world leader bringing democracy, stability, and open markets to the world.

Of course a lot of these ideals were shaken terribly by the Vietnam War. Minorities and Black folks have always had some skepticism or outright objection to this story — it didn’t apply to them equally. While there have been big victories for women and minorities in the 20th century such progress could not be taken for granted at the turn of the millennium.

Manifold crises hit. Wars. Financial crashes. Addiction epidemics. A pandemic.

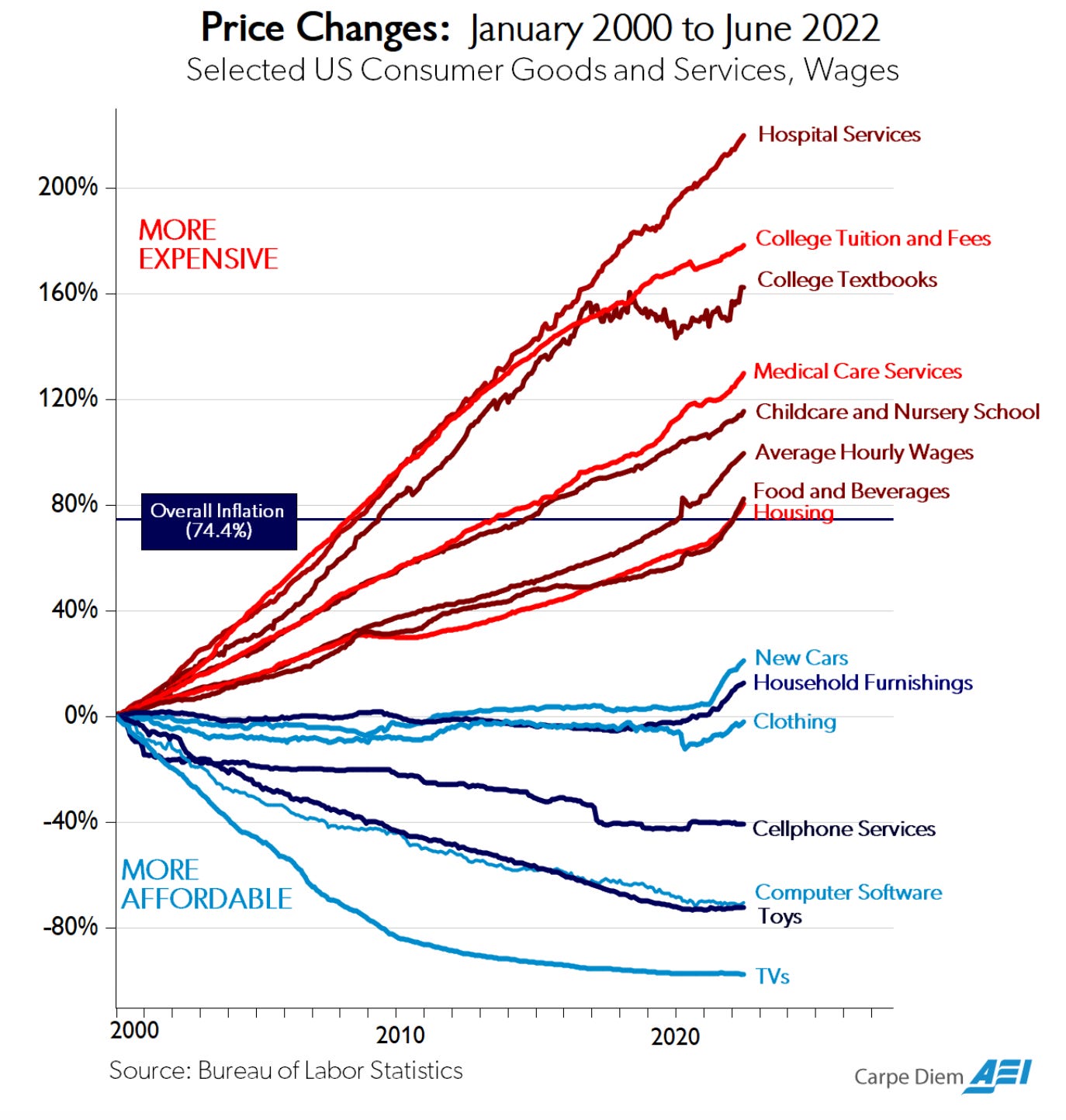

There are so many experts who have expounded upon the loss of institutional trust and widening inequality in the wake of such experiences, so I won’t enumerate them. I will say that civil rights aren’t felt and basic services feel hard to afford. Raging income inequality has cut into social progress; just one data point that is a portrait: Black homeownership rates today are just about as low as they were in the 1960s when it was legal to racially discriminate. Roe v. Wade was overturned. Essential goods and services are more expensive, even if TVs are cheaper.

The story about “getting ahead” apparently was subverted to affording a new iPhone, not better health or education. Today, working hard does not mean you’ll even keep apace with inflation.

But you know these problems — they have been best enumerated by populists Left and Right since 2015. They acknowledged the Authenticity Gap and started telling new deep stories about how America and the world worked, trying to bridge that gap between experience and reality.

The populist story helped bridge the Authenticity Gap that plagued us for so long. That story was this: a small number of selfish elites in government, liberalism, and corporations are duping regular people and selling out America for personal gain.

The Rewriting

However, even disruptive populism will have its limits. At a certain point, blaming things on elites will get in the way of the disruptors who will find themselves in charge. We will need new assumptions, new stories, new frameworks for how to close the Authenticity Gap between the stories we tell ourselves about how the world works and our experience of it.

As a thought exercise, I enumerate some of those questions here, with italicized questions for politically minded messengers:

Economics: How does the 21st century economy work and who benefits from it currently? Large asset managers have essentially created stabler markets that don’t perform by 20th century capitalist logics. Supply and demand? Free trade? Pff. These turns of phrase feel empty now. What would an economy that benefits the many, not just the few, look like?

Climate: Climate change is real and the consequences of it are increasingly hitting the developed world. But what mitigation and prevention methods feel within reach? Does exchanging carbon credits feel like a sham to you too? Can we help Americans survive climate change, as well as curb it?

Geopolitics: Is American foreign policy designed to help America or AmeriCANS? Is this to benefit the state and capitalism, or the people? Currently, there is mistrust in the logics of American internationalism. Can foreign policy benefit Americans, not just America?

Health: What does it mean to be healthy and what is the role of the state in ensuring or enabling that? Is “health insurance” really “healthcare?” Can quality of life improve for the many, not just through providing insurance (that may not even save you from medical bankruptcy) but good and accessible services? Do we have a story of what societal and individual healthiness is, beyond fitness?

Citizenship and Immigration: What is an “American” is a never-ending site of contestation in this country. Who should belong, when, how, and why? What does a citizen get that is special, if at all, compared to residents or refugees? Do we know what citizenship is in 21st century America?

Religion/Spirituality: What is the soul of an American? The rise of New Age psychedelics and spirituality, as well as speculative utopian technology, indicates a yearning for a beyond. Does American statecraft have a role in defining the American soul?

The MAGA movement had some deep stories that were surprisingly consistent about each of these issue areas. They were populist and verging sometimes on conspiratorial or patriarchal, but there was a kind of consistency.

Is there a clear articulation of opposing deep stories to close the Authenticity Gaps that tear through each of these issue areas?

A Quick Note on the Data and Vibes Trap

But Danielle! If we just target some messages to the right people or have the right “vibes” we can win! Authenticity is a lie anyway!

Look. Any political apparatus needs good data, good messaging, and good styles delivered to clearly identified audiences. But I ask again, Why and for whom? This is where the cultivation of deep stories is important. Those stories cannot be manufactured in a lab, but will evolve from debate, conversation, investment among and within groups of stakeholders who want something that “the other side” isn’t offering. In a word, culture will emerge when cultivated in real, participatory human networks.

You cannot “message” your way out of this if you have untrustworthy messengers and the same leadership that is failing forward. Nor will just having good “vibes” work — and lord knows I was one of the first to write about “vibes in politics” before it became daily parlance. A “vibes” only approach just feels like falling out of a coconut tree. Nor can you “test” your message to perfection — as The Atlantic reports was a tension among Democratic leadership in the 2024 presidential election (doesn’t this sound like 2016 Clinton campaign debates between intuition-centered John Podesta versus garbage-in-garbage-out data guy Robbie Mook? Or am I too obsessed with the rhymes of history?) At a certain point, you also need to have a long game, a deep story, that is told by fresh leaders who were not responsible for any of (~waves hands~) this.

Vibes and messages are built off of deep stories that can help explain a world that aligns with our general experience of how the world works. These deep stories should also have a north star that is explicit and consistent, and told by people who feel authentic, that is to say, distinct from the past. What could that look like? What could closing the Authenticity Gap with a deep story, backed up by data, style, and vibes? That is for another blog post, another day.